Here we go again.

With California considering a new ‘Journalism Preservation Act’, which would essentially force Meta to pay for news content that users share on Facebook, Meta has threatened to ban news content entirely in the state – which is now a common refrain for Meta in such circumstances.

California’s Journalism Preservation Act aims to address imbalances in the digital advertising sector by forcing Meta to share a cut of its revenue with local publishers. The central argument is that Facebook benefits from increased engagement as a result of news content, and thus gains ad revenue as a result, as Facebook users share and discuss news content via links.

But the flaw here, as Meta has repeatedly argued – when Australia implemented its similar News Bargaining Code in 2021, and when Canada proposed its own variation – is that Meta doesn’t actually glean as much value from publishers as they do from Facebook, despite what the media players continue to project.

As per Meta spokesman Andy Stone:

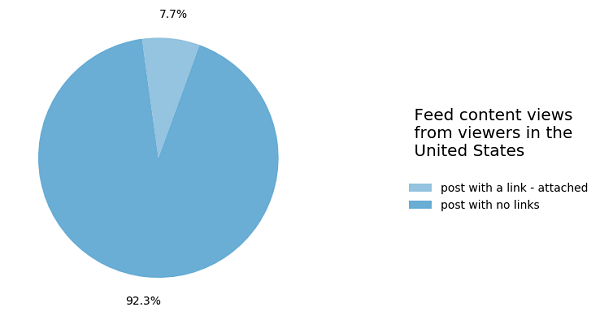

As noted, the basis for all of these proposals is that Meta benefits from publisher content, so it should also pay to use it. But with Meta’s own insights showing that total views of posts with links (in the US) have declined by almost half over the last two years, Facebook is actually becoming increasingly less reliant on such over time.

Still, that hasn’t stopped the big players from pushing for reforms, and using their influence over political parties to seek more money, as their own income streams continue to dry up due to evolving consumption shifts.

Which has, of course, benefited online platforms, and over time, Meta and Google have gradually eaten up more and more ad market share, squeezing out the competition.

That leaves less money for publishers, which means less money for journalists, and thus, less comprehensive and informative local media ecosystems.

The basis for further investment in local voices makes sense – but the idea that Meta should be the one funding it is flawed, and always has been in every application of this approach.

Yet despite its protests, when Meta has been forced to concede, local media groups have benefited.

In Australia, for example, where Meta did actually ban news content for a time, before re-negotiating terms of the proposal, the Australian Government has since touted the success of the initiative, claiming that over 30 commercial agreements have been established between Google and Meta and Australian news businesses, which has seen over $AU200 million being re-distributed to local media providers annually.

Really, Meta probably should have stood its ground, and refused to pay at all, because even in a watered-down variation of this proposal, millions has filtered through to publishers, which is what’s empowered Canada and now California to try their hand at the same.

But it remains a flawed approach, which, if anything, will only prompt Meta to phase out news content even more, as it continues to focus on entertainment, largely driven by Reels engagement.

Meta actually sought to cut political content from user feeds entirely over the past year, but has since eased back on that push, after user feedback showed that despite political posts causing angst and argument, people do still want some political discussion in the app.

But it’s in clear decline, which means that Meta needs news posts less and less, as the broader focus for social apps moves more towards content discovery, and away from perspective sharing.

Which means that California, and Canada, are in increasingly weaker positions as they seek to negotiate these deals.

It could be difficult for Meta to initiate a state-wide ban on news content, but I do think that they could, and would do so, if push comes to shove.

Which will only hurt local news publishers through reduced traffic – and it’ll be interesting to see if California and Canada do seek to enact these revenue share pushes, despite Meta’s threats.