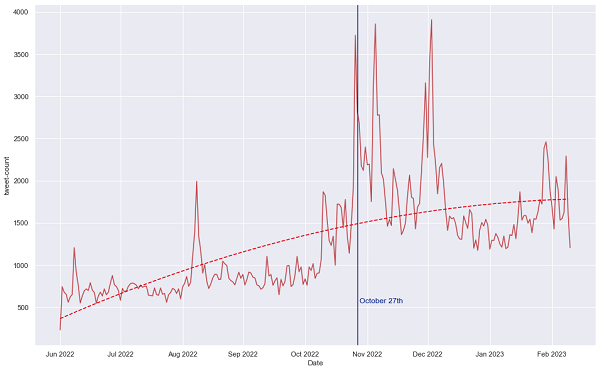

There’s been much discussion of late about the rate of hate speech on Twitter, and whether there’s more hateful content being shared in the app under Elon Musk.

Given that Elon has overseen the reinstatement of tens of thousands of previously banned users, and has stoked anti-government and anti-establishment sentiment with his own tweets, it makes sense that such incidents would be on the rise, while Musk has also implemented a more open speech approach, which is designed to allow more types of comments and content to remain active in the app, as opposed to taking such down.

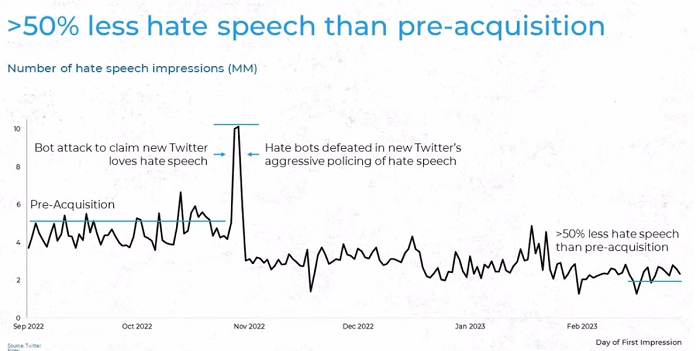

Weighing these elements, hate speech would, you would think, have increased – yet according to Twitter, it’s actually declined.

But third-party analysis suggests the opposite, with rates of hate speech reportedly increasing on ‘Twitter 2.0’.

So which is true, and why do these reports vary so significantly – and should you be concerned, as an advertiser, that your ads may be displayed alongside hate speech in the app?

The variance in reporting likely comes down to different reporting methods.

In one third-party analysis report, conducted by The Center for Countering Digital Hate (CCDH) back in December, which found that slurs against Black and transgender people had increased by some 60% since the Musk takeover, it notes that:

“Figures cover all mentions of a given slur or its plural equivalent in English-language tweets worldwide and include retweets and quote retweets.”

So it’s based on key term mentions only, and the rates in which each of these terms has appeared in the app. Which is a fair proxy for measuring the relative frequency of such, but Twitter’s own analysis, which was conducted by partner Sprinklr (published last month), takes a more nuanced approach.

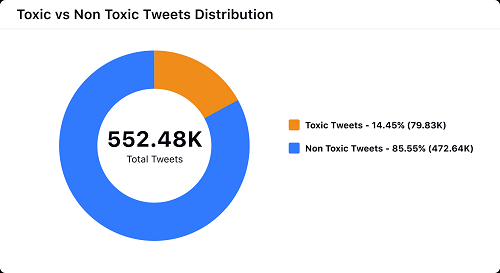

“Sprinklr’s toxicity model analyzes data and categorizes content as ‘toxic’ if it is used to demean an individual, attack a protected category or dehumanize marginalized groups. Integrating factors such as reclaimed language and context allowed our model to eliminate false positives and negatives as well. The model uses AI to determine intent and context around the flagged keywords, to help brands understand what is really toxic.”

So Sprinklr is measuring not only key terms, but also how they’re actually used, which it says is a more accurate way to track such activity.

Some derogatory terms, for example, may be used within a context that’s not offensive – which, in fact, Sprinklr says is the majority.

“The percentage of tweets identified as toxic in the data set containing slur keywords was in the range of ~15% over the analyzed time frame. Despite every tweet containing an identified slur word, they are primarily used in non-toxic contexts like reclaimed speech or casual greetings.”

That provides some insight as to why Twitter says that hate speech has actually decreased, because with more advanced reporting, which takes into account context, not just mentions, the overall rates of hate speech, as it measures it, are declining, even if, as some reports have suggested, mentions are increasing.

Yet, that doesn’t account for all the third-party analysis out there. In March, the Institute for Strategic Dialogue (ISD) published its own report which showed ‘a major and sustained spike in antisemitic posts on Twitter since the company’s takeover by Elon Musk.’

And unlike the CCDH report, ISD’s data does reflect nuance, similar to the Sprinklr process.

“This is a research challenge that forces us to go far beyond simply counting the frequency of certain words or phrases, and instead use machine learning and natural language processing to train models and workflows capable of handling complex and multi-faceted forms of language, meaning and expression.”

As you can see, based on ISD’s findings, Twitter is hosting more hate speech, within specific parameters. ISD has also noted that Twitter’s now removing more content, so it is taking action. But it is also seeing more activity, which relates to antisemitic tweets specifically, but even at more limited scale within the broader hate speech element, that’s obviously a major concern.

So what’s actually correct, and how does that relate to your promotions?

A lot of this will largely come down to your perspective, and how much trust you place in Twitter’s team to combat this element. Twitter says that hate speech, overall, is down, but there’s no transparency on how it’s come to these figures, while third-party reports measuring specific elements say it’s up, via varying methodology.

Twitter does now offer more ad placement controls and brand suitability measures to provide more reassurance to advertisers that their promotions won’t be displayed alongside hate speech. But this is a key factor in why many Twitter advertisers have pulled back from the app, and continue to do so.

Should that be a concern for your promotions? Understanding the variance in reporting, when viewing such data, is key to contextualizing this element.