Amid ongoing concerns about its data gathering processes, and its possible linkage to the Chinese Government, TikTok’s influence continues to grow, with the platform now a key source of entertainment for many of its billion active users.

And it’s not just entertainment, TikTok is also increasingly being used for search, with Google reporting earlier this year that, by its estimates, around 40% of young people now turn to TikTok or Instagram to search for, say, restaurant recommendations, as opposed to Google Search or Maps.

And now, TikTok is also becoming a source of news and information, as more news organizations look to lean into the platform, and establish connection with the next generation of consumers.

That’s the focus of the latest report from the Reuters Institute, which looks at how people are using TikTok for news content, and which sources are playing a role in shaping their opinions in the app.

You can download the full, 38-page report here, and it’s well worth a read, but there are two specific elements that are worth highlighting to help better understand and contextualize the TikTok shift.

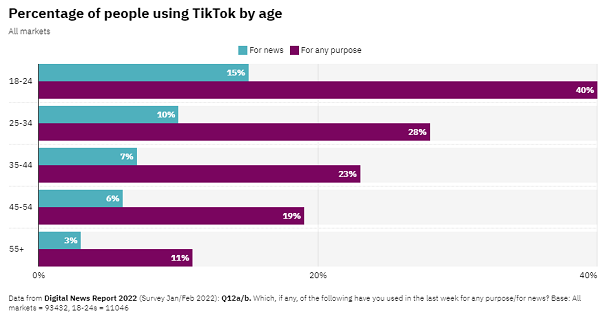

First off, there’s this chart, which looks at the percentage of people who are using TikTok for news content in each age bracket.

As you can see, younger users are increasingly turning to TikTok to stay informed of the latest news updates. Which is a significant shift, and not just for news publishers looking to connect with their audience, but also in terms of broader impacts, and how young audiences are staying in touch with the latest happenings.

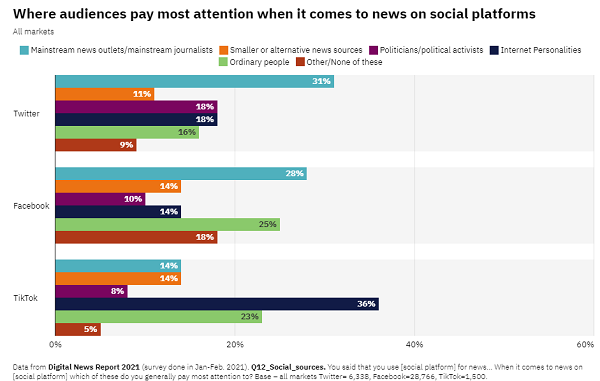

Which then leads into this second chart:

As you can see, it’s not mainstream news sources that are the primary sources of news content on TikTok, its ‘internet personalities’ followed by ‘ordinary people’, with traditional journalists and publications much further back.

That’s a significant trend, which could reflect a broader distrust of mainstream media outlets, and the information presented in the news as we know it.

Now, younger audiences are more reliant on their favorite influencers to act as a filter, of sorts, to help highlight the news of most relevance – which could be good, in that it facilitates a new angle on the big stories each day. But it could be bad, in that the news they present and discuss is then based on the personal bias of each influencer, which is arguably a less transparent process than mainstream news outlets.

But that also depends on your perspective. Journalists, for the most part, work to uphold standards of integrity in their reporting, in order to limit the influence of personal bias, and present the key information within their updates. But increasingly, many news outlets have leaned into more controversial takes and opinions. Because that’s what works best with social media algorithms – you’re going to generate much more engagement, and thus, reach, with a headline that says something like ‘The President hates farmers’ as opposed to a more balanced report on the latest agricultural policy.

Many outlets have essentially weaponized this, and seem to employ partisan takes as a key element in their coverage, again, in order to maximize reader response, to get people commenting and sharing, and prompt more clicks.

Which definitely works, but it’s this approach that’s likely turned many younger consumers away from mainstream coverage, while the rising use of TikTok overall means that, one way or another, they’re going to get at least some news content there anyway.

Which could be a concern. Again, amid ongoing questions about the influence of the Chinese Government on the app, it seems like it should be a significant consideration that more and more young people are leaning on the app to stay informed about the latest news topics.

The report also looks at how news publishers are using TikTok, and what specific approaches are driving the most success.

Their conclusion:

“There’s no single recipe for success. Many publishers use a strategy based on hiring young creators who are native to the platform and its vernacular. This approach has connected strongly with audiences and brought critical acclaim but can make it harder to re-version content for other social platforms. Others have focused on showcasing the assets of the entire newsroom, including more experienced correspondents and anchors, delivering greater scale and flexibility but often without the same personal touch.”

So using platform-native influencers, and those more savvy with TikTok-specific trends, can help to increase engagement and performance. But there’s no definitive TikTok playbook, as such, that will lead to guaranteed, sustained success.

Which, in some ways, is because that’s not how TikTok is built. Unlike other social media apps, TikTok isn’t designed to get you to follow the people and companies that you like, in order to essentially curate your own experience.

On TikTok, the aim is to show you the most entertaining content, from anyone, in alignment with your personal interests, which you express by simply using the app. By expanding the pool of potential content to everybody, that gives TikTok’s algorithms a lot more ways to keep you glued to your feed – but the flipside is that it also makes it much harder for creators and brands to establish a following, and keep their audience coming back, as they can on other apps.

That puts more focus onto each post itself, and how entertaining your latest update is. Which is better for TikTok’s ecosystem in general, but it also means that there are more challenges in maintaining reach and resonance in the app.

That’s true for news organizations, but it’s also true for brands, because you can’t just get people to follow your brand in the app and hope that they’ll then see everything that you post.

On TikTok, it’s a new competition, every day, and if you’re not entertaining, and holding engagement with each update, you’re going to lose, on that day at least.

You can download the full Reuters Institute ‘How Publishers are Learning to Create and Distribute News on TikTok’ report here.