This could be a significant problem for Google, and for advertisers that have been using its video ad campaigns.

According to new analysis, conducted by ad intelligence firm Adalytics, around 75% of ads purchased through Google’s TrueView video campaign offering have been displayed on surfaces that do not meet Google’s standards for ad placement, in which Google promises specific parameters for the viewer experience and exposure within these campaigns.

As per Adalytics’ findings:

“For years, significant quantities of TrueView skippable in-stream ads, purchased by many different brands and media agencies, appear to have been served on hundreds of thousands of websites and apps in which the consumer experience did not meet Google’s stated quality standards. For example, many TrueView in-stream ads were served muted and auto-playing as out-stream video or as obscured video players on independent sites. Often, there was little to no organic video media content between ads, the video units simply played ads only.”

As Adalytics notes, Google’s standards for TrueView video campaigns include specific parameters around qualified ad views, based on exposure across various platforms.

As explained by Google:

“TrueView gives advertisers more value because they only have to pay for actual views of their ads, rather than impressions. Viewers can choose to skip the video ad after 5 seconds. If they choose not to skip the video ad, the YouTube video view count will be incremented when the viewer watches 30 seconds of the video ad (or the duration if it’s shorter than 30 seconds) or engages with your video, whichever comes first. Video interactions include clicks to visit your website and clicks on call-to-action overlays (CTAs).”

Because of this higher engagement threshold, TrueView campaigns have been a popular option among bigger spending brands, but if this new analysis is correct, those businesses have not been getting what they’ve paid for in using this approach.

According to the Wall Street Journal, that could end up costing Google billions in refunds, while also significantly harming the credibility of its ad business.

As you may expect, Google has refuted the report, and criticized what it’s called an ‘extremely inaccurate’ portrayal of its systems.

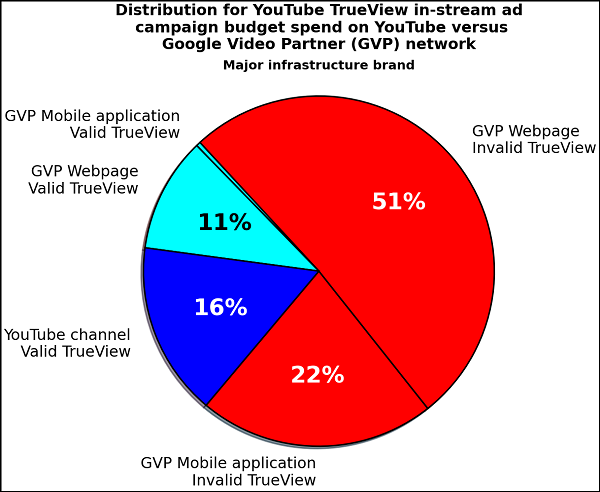

The main sticking point for Google is that the report, in its view, overstates the placement of video ads via the Google Video Partner (GVP) network.

As explained by Google:

“The report wrongly implies that most campaign spend runs on GVP rather than YouTube. That’s just not right. The overwhelming majority of video ad campaigns serve on YouTube. Video advertisers can also run ads on GVP, a separate network of third-party sites, to reach additional audiences, if it helps them meet their business objectives. While only a small percentage of video ads appear on GVP, it’s effective: we’ve seen adding GVP to YouTube campaigns increases reach by over 20% for the same budget.”

Google further claims that over 90% of ads on GVP are visible to people across the web, and that advertisers only pay for ads when they are viewed, while it also supports independent third-party verification from various providers to assure its viewability claims.

Either way, the report once again highlights lingering questions within the digital marketing space about viewability metrics, and what exactly qualifies as a valid ‘view’ within this context.

Twitter, as another example, has also come under scrutiny of late due to its counting of video views for its in-tweet listings, with a ‘view’ in this context ticking over once a second is played on screen.

The variance in how platforms measure such has led to confusion over what this stat even means – though in this specific context, Google has communicated very clearly that a higher level of engagement is required to trigger a view for these campaigns.

The findings will now come under more scrutiny, while they’ll also force Google to reassure its ad partners, and provide more insights into its processes, to show why the findings are not reflective of its systems. Based on Google’s response, it seems confident that it has no case to answer, but the examples and notes presented in the report do suggest that there’s more to it than a generic hit piece.

We’ll keep you updated on any progress.