If you’re wondering why social division feels more prevalent and present than ever before, this could provide some insight.

According to a new study, which analyzed over 105k variations of story headlines from Upworthy.com, stories with more negative terms in the headline drive more clicks, while positive terms decrease engagement, based on user response.

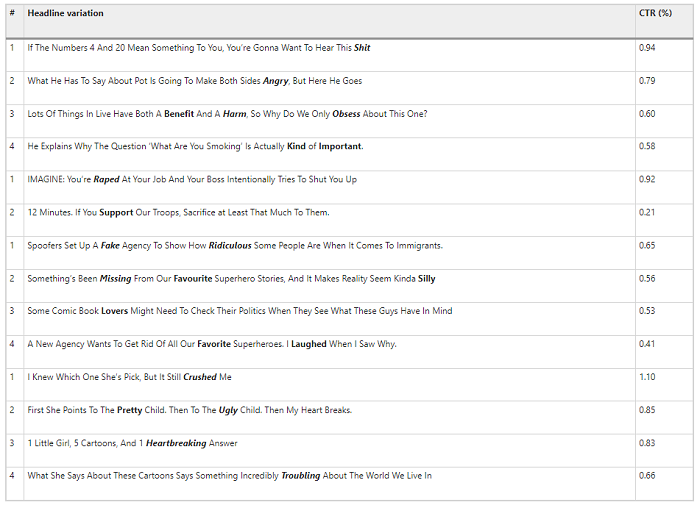

The study analyzed headline variations applied to Upworthy posts, in order to glean more insight into how changing the terminology of the headlines alone can impact click-through rates (CTR).

As per the report:

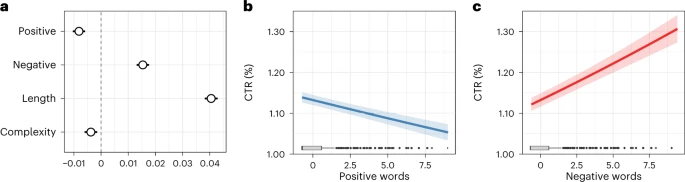

“Although positive words were slightly more prevalent than negative words, we found that negative words in news headlines increased consumption rates (and positive words decreased consumption rates). For a headline of average length, each additional negative word increased the click-through rate by 2.3%.”

The study used keyword analysis to detect negative terms in headlines, with words like harm, heartbroken, ugly, troubling, and angry in the negative term corpus.

As you can see in this example, the addition of these negative terms correlated with an increase in website clicks, while the use of positive terms – including benefit, laughed, pretty, favorite, and kind – had the opposite effect.

Which is not overly surprising. It doesn’t take a genius to see that divisive, argumentative takes generate more engagement, and with social platforms looking to incentivize more time spent in their apps, that engagement then tells their respective algorithms that this story is interesting, which then sees it distributed to more users, getting more reach and exposure.

Using raw engagement data as a proxy for user interest has been a toxin that’s poisoned online discourse over time. And with online sources increasingly becoming the news and entertainment providers of the day, that’s led to even more hate and division, as fueled by what’s driving interaction, based on pure data points, as opposed to analyzing what that engagement actually is.

But algorithms, of course, aren’t able to identify context – they’re binary systems that can only determine whether each post is generating likes, comments and shares, or not. Various proposals have been put forward on how to better incentivize more positive online behaviors, but thus far, under pressure from shareholders and the need to demonstrate growth, no platform has been able to action such effectively.

Which means that argument and anger wins out – as further underlined by these stats.

And there may be a good, evolutionary reason for such.

“Negative information may be more ‘sticky’ in our brains; people weigh negative information more heavily than positive information, when learning about themselves, learning about others and making decisions. This may be due to negative information automatically activating threat responses – knowing about possible negative outcomes allows for planning and avoidance of potentially harmful or painful experiences.”

But whatever the underlying logic, the bottom line finding is that a larger proportion of negative words in your headlines will increase the likelihood of users clicking through on your posts.

“A one standard deviation larger proportion of negative words increases the odds of a user clicking the headline by 1.5%. For a headline of average length (14.965 words), this implies that for each negative word, the CTR increases by 2.3%. In contrast, the coefficient for positive words is negative (???? = −0.008, SE = 0.001, z = −9.238, P < 0.001, 99% CI = (−0.010, −0.006)), implying that a larger proportion of positive words results in fewer clicks.”

It’s a sad statement on online discourse, and how appealing to such responses drives clicks. And of course, we know this. Many news organizations now seem to approach every news story with the worst possible take, in the hopes of sparking argument and discussion, which will inevitably get them more traffic.

Does it matter if it’s true, if it’s accurate? I suspect, in many cases, it absolutely does not, which has driven a whole new wave of media distrust, and movements of people who are convinced that they’re being sold lies, by one side or another.

Which is likely true, but if you’re looking for the culprits, I suspect the more controversial pundits, the ones benefiting most from such arguments, are more likely to be peddling lies and misinformation.

Follow the money and you’ll find the truth – while for content creators, it also provides more context to consider in your own headlines, if you want to drive clicks.

That’s not to say that you should be controversial for controversy’s sake. But maybe, focusing on the negative in your posts could have a positive impact.

You can read the full study, posted on Nature, here.